Market Summary: 3Q–2022

The Pain of Trying to Get Back In Sync

The third quarter further contributed to what was already a pretty difficult year for markets across the board. Everything was down: stocks, bonds, and even commodities. Modern portfolio theory taught us that if we diversify our portfolios using noncorrelated investments with different sources of returns, when some of those elements zig, others will zag. Ultimately, this diversification should help mitigate damage to the portfolio. However, this year, that has not been the case, as correlations between stocks and bonds have risen, leading both to fall in value at the same time.

How did we get here? During the global COVID shutdowns in early 2020, demand for many goods and services plummeted, so suppliers (e.g., manufacturers and service operators) reduced staff and production levels. The unprecedented government stimulus that followed and the swift reaction by healthcare companies to find ways to fight the virus allowed economies to reopen rather quickly. But after decades of manufacturers pursuing ever-lower costs via globalization and fine-tuning just-in-time shipping, the disruption to that logistical metronome proved difficult to get everything back on tempo. It didn’t help that fiscal and monetary authorities (in hindsight) over-provided assistance.

So, we find ourselves in a situation where (in economic terms), demand is higher than supply. This condition typically leads to higher prices (i.e., inflation). Many economists believed early on that this inflation would prove “transitory”, and that once we got employees back to work and production levels back up, supply and demand would come back into balance. However, this has proven to be easier said than done, because for a myriad of reasons 1) a large number of workers left the labor force and 2) other workers took the opportunity to transition into different lines of work. At the same time, higher energy prices began to creep into other goods.

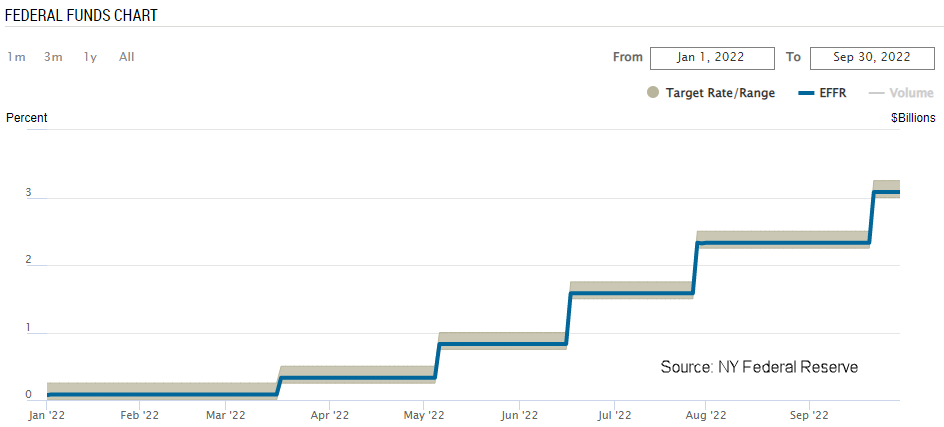

To combat stubbornly high inflation, the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates early this year. Initially, 25 and 50 basis point rate hikes were meant to remove some of the overly accommodative monetary stimulus that might have been contributing to inflation. But with subsequent inflation figures still coming in elevated, the Fed has turned to more aggressive 75 basis point rate hikes for each of the last three meetings (see image below).

The Fed Funds Target range (the overnight rate at which banks lend money to each other, the movement of which has ripple effects for all other interest rates in the economy) currently stands at 3.00-3.25% - significantly higher than the 0-0.25% range where we began the year. However, this is still well below the Fed’s estimate of where that range will ultimately top out. The FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee, the interest rate policymaking committee of the Fed) currently estimates that the Fed Funds Rate will end 2022 between 4.10-4.40% (another 110-115 basis points higher from here) and get as high as 4.40-4.90% sometime next year. In short, there’s still a way to go before the Fed is done hiking rates.

The economic problem with hiking interest rates is that it reduces economic activity by raising the cost to borrow money. From a business perspective, this makes some projects more expensive, rendering some unprofitable. Unprofitable projects get scrapped or delayed until the calculus can justify an acceptable return on capital for the business. From a consumer perspective, it makes it more expensive to finance large purchases (e.g. autos, homes, appliances). Case in point is the housing market. The national average rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage has risen from 3.11% at the beginning of the year, to 6.70% at the end of the third quarter. Along the way, we’ve seen housing activity trail off in nearly every measure. New home sales/starts/permits and existing home sales are all down year-over-year, while months of inventory on the market has crept higher. You can imagine what a decline in housing activity alone will do to the incomes of residential construction workers, mortgage bankers, real estate agents, furniture/appliance retailers, etc. And that is how interest rate hikes cool economic activity – what economists term “demand destruction”.

Surely the Fed wouldn’t let the economy fall into recession, right? It could, and don't call me Shirley. Several FOMC members, including Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, have made comments acknowledging that “some pain” is on the horizon for the US economy, and that “there is still work to be done”. To understand why, it’s important to understand that the Fed has two mandates: full employment and price stability. The existence of this magnitude of inflation is evidence that the second mandate is not being achieved, and ironically, it may be partially due to the condition of the first mandate (i.e., the job market being too tight due to post-lockdown labor market transitions). Among the two mandates, it’s clear that getting inflation under control is the current priority for the Fed. For this reason, more economic analysts and Wall Street strategists are calling for a recession within the next year or so.

Where does that leave investors? Well, on a year-to-date basis, disappointed. Year-to-date through the end of the third quarter, US stocks (as measured by the S&P 500) were -23.9%, while international developed and emerging market stocks (as measured by the MSCI EAFE and MSCI EM Indices, respectively) were -27.1% and -27.2%, respectively. As mentioned earlier, bonds didn’t do much to help the situation. The aggressive rise in interest rates throughout the year has left the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index -14.6%, because when interest rates rise, bond values/prices fall. This brings us back to the correlation issue. Bonds and stocks are both falling in value because the Fed keeps raising interest rates.

When will this pain end? When the Fed feels like it has inflation sufficiently headed in the right direction, it should begin to slow its rate hike cycle. This is why the market seems so volatile – where the market falls 5% one week and then rises 5% the next week – because traders are trying to guess when the Fed will slow or pause (aka “pivot”). This creates a “good news is bad news” environment, where the market associates good economic news with a bad outcome from the Fed (i.e., they’ll keep hiking rates). In our opinion, the mission to fight inflation is too important to the Fed to pause anytime soon, and multiple FOMC speakers have reiterated as such many times in recent speeches. For that reason, we expect to continue to see this tug-of-war for the next few months.

That should leave short-term traders sufficiently busy, but for long-term investors, we would highlight a few silver linings. With stocks now solidly in bear market territory (defined as down 20%+ from their prior peaks), that drawdown has resulted in stocks moving from “expensive” a year ago, back into the “fair” range based on a forward price-to-earnings basis for the first time since the pandemic began. That bodes well for long-term investors because research shows that buying stocks at lower valuations results in better long-term returns. And while it’s notoriously difficult to predict market movements over short time horizons, when we look at longer time horizons (like those for long-term investors), investing in stocks pays off. We encourage investors to remain disciplined, rebalance and tax loss harvest where appropriate. Volatility may last for a little while longer, but once we get supply and demand back in sync, this too shall pass.